Shamayel

Shamayel Baghbani lived through war, loss, and silence in a remote Iranian village. This is a remembrance of her life, and others like hers, lived in history’s margins.

“Shamayel,” a woman called from the old rustic house. It had been give-or-take twenty days since Norooz of 1938. All the children of the village were playing amidst the walnut trees and jumping in the little rivers brimming with water coming from the melted snow on the top of the mountains. A little girl gathered her doll and said goodbye to her friends.

Her mother, waiting at the door for her, pulled her aside and told her to go wash off the dirt from her hands and face. She said that she had had a special visitor, a suitor. She was only nine years old.

Shamayel and Sedalsan were married when she was twelve years old. In the wedding ceremony, when they gave her the Quran to read as the wedding vows were being read by the imam, she didn’t know how; so she whispered some verses that she knew by heart.

Sedalsan was a shepherd and had a very traditional view on life. It was said about him that he treated his herd like people and sometimes treated people like they were no more than animals. An even-tempered but serious man who didn’t talk much but expected his few words to be followed to a T. A true patriarch if there ever was one.

She, on the other hand, was brimming with poems, stories and verses; she never got to go to school, her father wouldn’t allow it. But for a few years, she went to a maktab where she wasn’t taught to read and write but absorbed all that she could by heart. Most of what she knew was passed on to her from her mother.

Her first child was born when she was fourteen years old: Khavar. Altogether, she had ten kids, some dead and some not; six survived to adulthood — two boys and four girls. The village had much to say about this.

Like most of the women in her area, she spent most of her day taking care of the children and eventually grandchildren, weaving carpets with her fellow housewives, peeling walnuts until her hands were a dark brown and lost their fingertips. She would occasionally herd the sheep in the mountains.

When she was sixty-five, she lost one of her eyes in a pressure-cooker accident; her neighbor had asked her to be in charge of her food when she had gone out. The pressure cooker exploded and cost her her left eye. By the time they could bring her to a hospital in the city, she had lost so much blood that her chador that was wrapped around her allegedly weighed twenty kilograms.

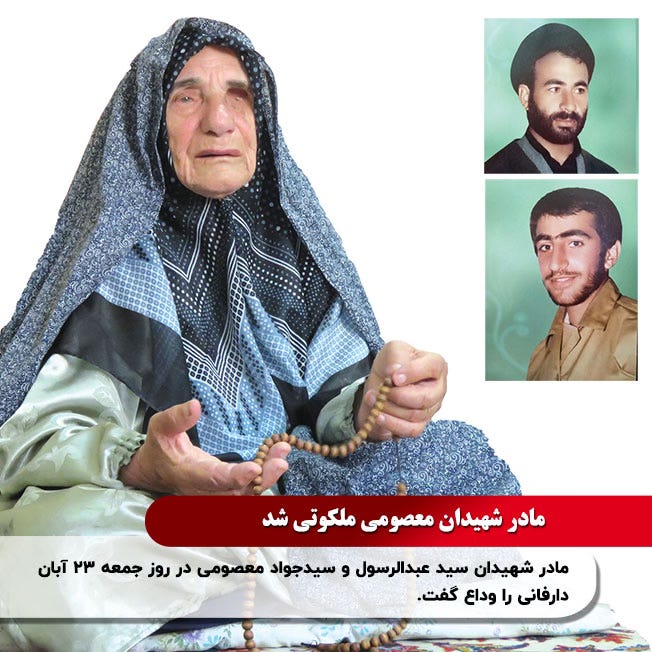

But then again, maybe she needed one less eye to be able to see and tolerate what was to come of her and her family. First, Khavar’s husband was lost to the Iran-Iraq war. Then her own husband was taken by cancer. Then her grandson’s body was brought back from the war. And finally, her two beloved sons — the only ones — were killed amid the last missions of the war. They were killed at the exact same time, fighting beside one another. Their story was more of a myth than an actual war story. Sedrasoul, the older one, the imam of his little village, the sergeant of the battalion, a pillar of his community, was said to have been seen wudhu-ing in his own blood amidst the chaos of the shell. And his little brother, who had left despite Shamayel’s reservations about him going, was killed right beside him. What was left of Javad’s nineteen-year-old body was brought back years later, but Sedrasoul’s was never recovered.

You could say that the shell broke her too. She was never herself again. She sat in the alcove of her house, the room that had a view of the garden of the pomegranate trees. She became much quieter overnight. She had her prayer beads in her hand, whispering under her breath, receiving the never-ending flock of guests. She would occasionally tell her granddaughters what to do and what to bring to the guests. The only times she spoke were when she would sing a ballad quietly or when she would tell vivid dreams of her dear sons in detail and shed tears out of her one eye. Her last years were spent in a dream where everybody was there, yearning for the years long gone — the dead children and loved ones behind a cloud of tears and surrounded by people.

“Shamayel.” All her life, she had disliked her name. She would always say, “When I die, don’t name your children after me.”

She was found dead in her corner of the alcove, amid the COVID pandemic. Her obituary in the local newspaper didn’t mention her name at all. It only said, “Mother of the Masoumi martyrs passed into the heavens.” Like the countless women who came before her — and the many yet to come — her name was buried by history, only spoken when tied to her sons. But her memory, the verses and poems she carried, lives on through those who survive her.

In loving memory of my great-grandmother, Shamayel Baghbani — a woman of verses, silence, and survival.